LYDIA TURCIOS

Art Director

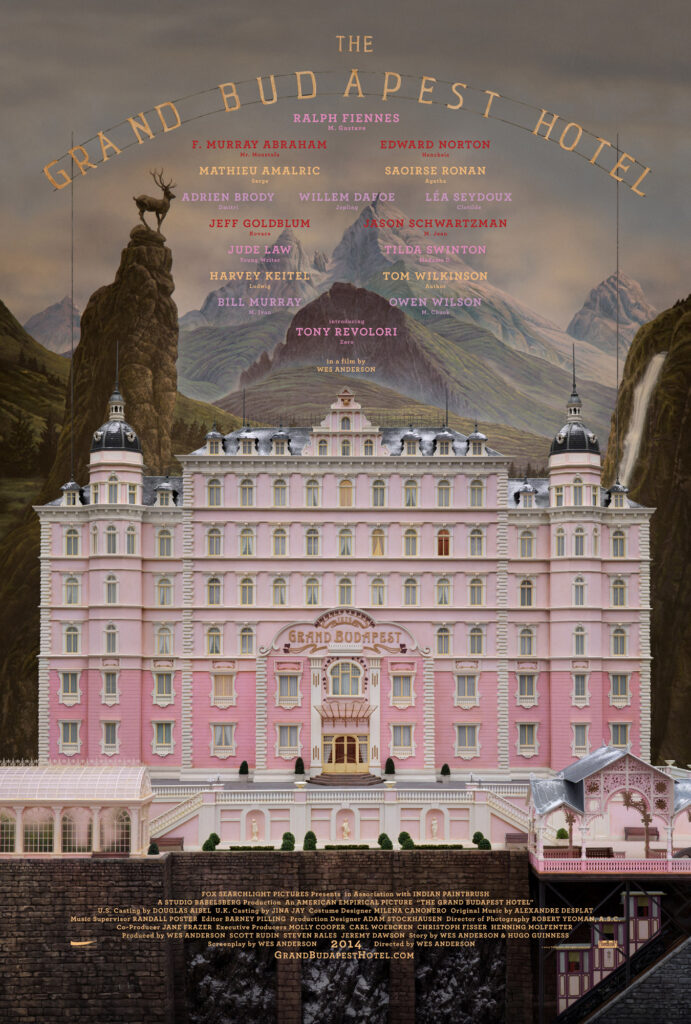

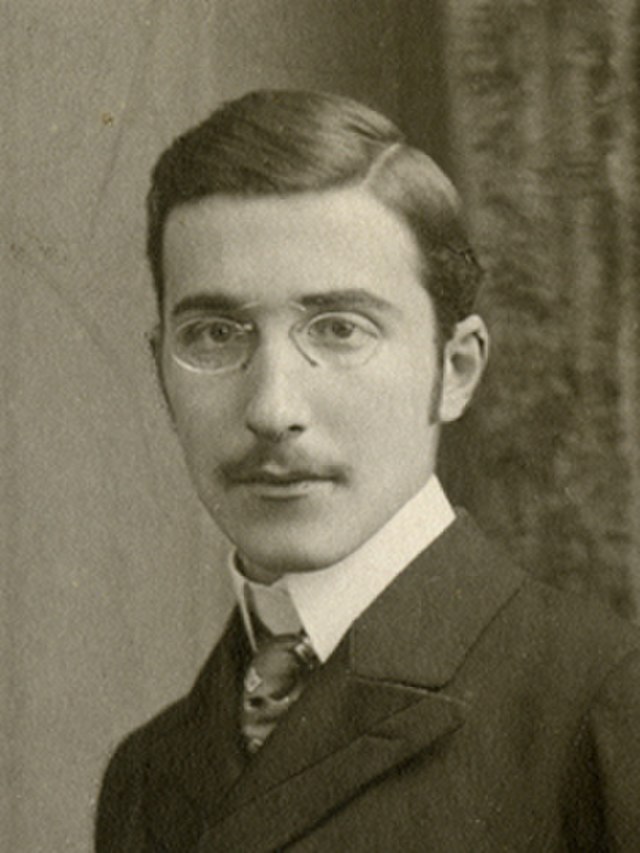

Wes Anderson is a master of color, composition and balancing comedy with tragedy. The jewel of his work is “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” released in 2014, in much the same way that the hotel is the jewel of Zubrowka, the fictional country in which the equally fictional namesake of the film makes home. Appreciations to Writers’ Ring for screening the film for the student body in celebration of Stefan Zweig’s 140 birthday, the author who inspired the film, and in honor of SUNY Fredonia’s archive collection of Zweig, one of the largest Zweig collections in the world.

The story is cleverly set up in a framing device within a framing device … within a framing device. First, a young girl reads a novel entitled “The Grand Budapest Hotel” at a memorial, which has been penned by an author who is dictating the story from a source of his own. Then, we meet the author as an elderly man in his study. He tells the reader — or viewer, in this case — of his stay at the hotel long past its prime. Now, we follow the young author during his stay at The Grand Budapest Hotel, and the movie starts in earnest as the protagonist, Mr. Moustafa, tells him of his time working as a lobby boy in the hotel’s heyday when he was more commonly known as Zero.

What follows is a flavorful blend of tongue in cheek comedy, art, stealing art, living in war-times, romance, immigration and, well, murder.

But first and foremost, it’s about a concierge. While Zero Moustafa is ostensibly our protagonist, the film is really about Mr. Gustave, his employer turned mentor and eventual friend, as he whirls about the hotel and it’s clientele. He makes for a unique leading man, mingling with the thugs and rakish criminals with the same levity and respect he grants the upper crust. Truly this network he’s made, which comes up many times in the film, is what keeps both him and his young mentee alive for so long.

“The Grand Budapest Hotel” has a unique look due to the way Anderson directs his live action films. The art direction is always top notch, sacrificing realism for painted backgrounds and copious amounts of practical effects that are obviously practical. Even the camera angles prioritize artistry before action. This film in particular does not disappoint in this field, with one of the best uses of color to convey meaning and mood. The drab and bogged down colors of the hotel as Zero describes it shows how far it’s truly fallen once we’ve seen the bright and lively tones of it in its prime.

The writing is similarly juxtaposed, snapping between physical comedy and heartfelt conversations on a dime, sometimes even at the same time. The finale is horribly bittersweet and open-ended, which is inline with the rest of Anderson’s films. It’s worth sharing two hours for, and the background knowledge provided by English professor Dr. Birger Vanwesenbeeck and students who worked with sources in the Zweig collection about the film’s creation truly rounded out the experience.