JULES HOEPTING

Managing Editor

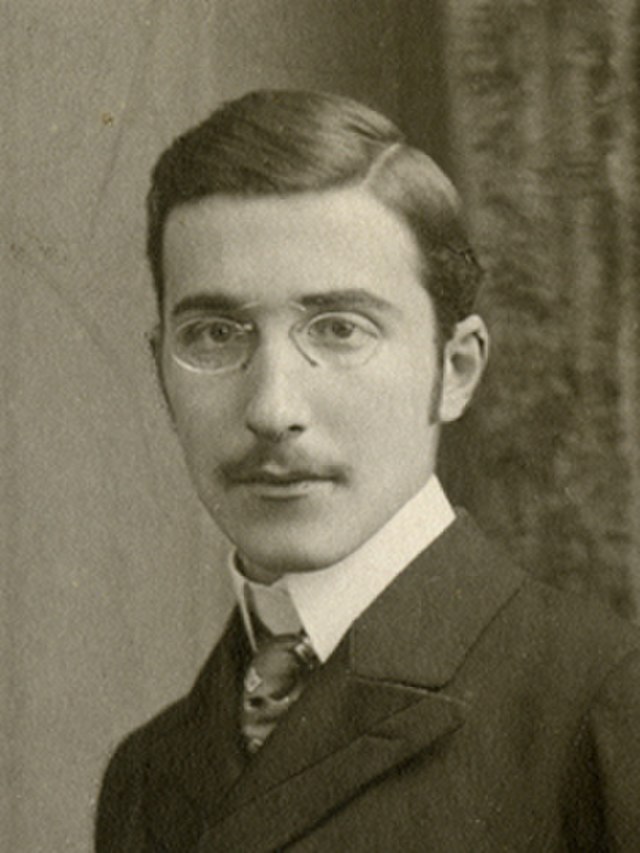

Reed Library is home to one of the world’s largest archive collections of Stefan Zweig. During the 1920s, the Austrian-born storyteller was the most translated author in the world.

Dr. Robert Rie, former Fredonia professor in the foreign language department, brought the Zweig collection to campus in 1967. Similar to Zweig and his first wife Friderike, Rie immigrated to the U.S. to escape Nazism. Rie was able to obtain papers from Zweig through Friderike and other donors added to the collection over time.

Ashley Halm, Devin White and Liv Frazer utilized this collection to create two new digital projects in a research practicum focused on Zweig instructed by Dr. Birger Vanwesenbeeck, English professor and Belgium native. The students’ projects are on the “Virtual Exhibits” webpage of Reed Library’s Stefan Zweig Collection, where they will be permanently hosted for future use by scholars.

Halm, junior English and theater double major, and White, junior English education major, created a narrated slideshow following Zweig’s 1939 US lecture tour across 18 cities. The tour is significant because it “reveals a lot about [Zweig’s] character and his attitudes,” and “the information about the tour is almost entirely located within our exhibit,” White said.

In addition to promoting his work, Zweig used to tour to present his views on art philosophy and his criticisms on how history is written from an ethnocentric perspective. Despite claiming to be “non-political,” Zweig presented “very anti-authoritarian” ideas due to his experience as a Jewish person during the rise of Nazism in Austria, according to White.

With “horrible irony,” Zweig also shared his racist beliefs that Black Americans would never be equal to whites. Interestingly enough, Zweig did not share these views while touring in the south, focusing those lectures on artistic creation.

“We look at these significant people in history, but we neglect to realize that a lot of them had no understanding of race relations,” White said.

Frazer, junior English major, created a slideshow relaying Zweig’s relationship to film. Despite Zweig’s stories inspiring over 80 films, Zweig wanted nothing to do with film adaptations. He felt film was not “hyper-realistic” and thought the new story-telling medium’s place was in surrealism, according to Frazer.

Frazer attributes Zweig’s stories’ popularity to their themes of universal human experiences in a time when sentimentalist, environmentalist and other “really lofty” works were prominent. Because his stories were rooted in human experience, people took away from the stories whatever they wanted, and in some cases, made films from their interpretations. This led to Zweig having not much control over his public image.

Overall, the students found researching Zweig’s life a valuable experience.

“For all his complications as a person and as a writer, [Zweig] still deserves to be studied and learned about by college students, not just scholars of European literature,” Halm said.

“I think the experience of working with primary documents is so important because we often think of historical figures as removed individuals that didn’t have feelings or thoughts or experiences. It’s hard to feel a correlation with somebody in a black and white photo,” Frazer said. “Seeing [Zweig’s] handwriting is a really powerful experience because it reminds you that every artist was also human.”