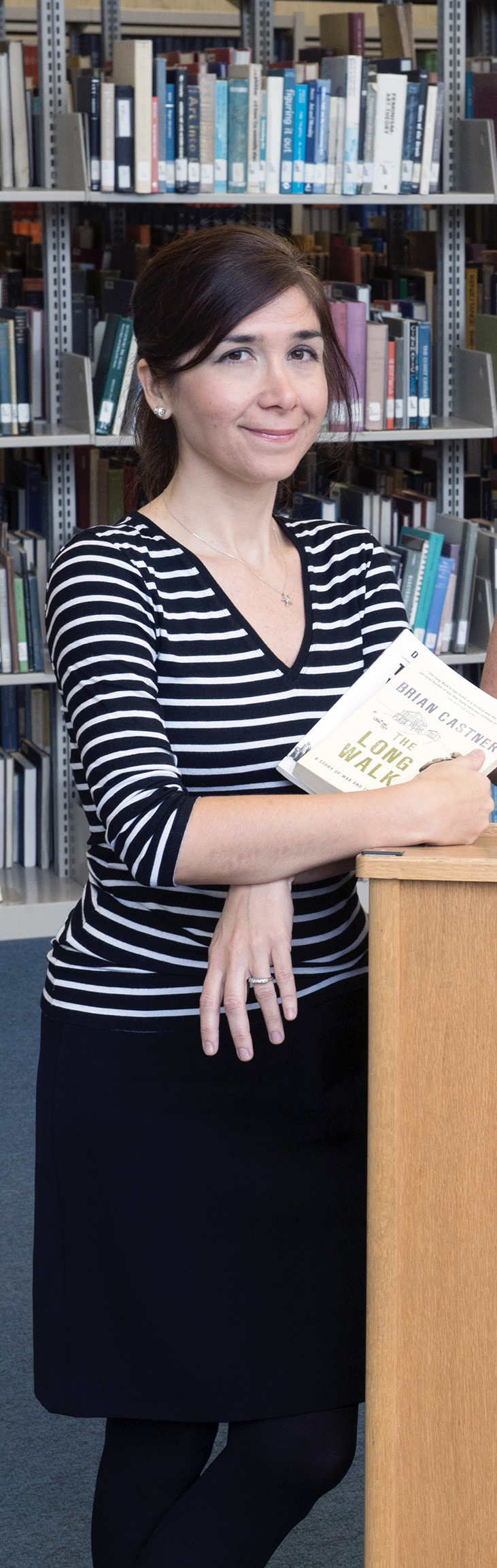

CAMRY DEAN

Staff Writer

For the past four months, Associate Professor of English Iclal Vanwesenbeeck has been living in Elbasan, Albania and teaching at Aleksander Xhuvani University.

In April of last year, Vanwesenbeeck was awarded the Teaching/Research Award for the U.S. Core Fulbright Scholarship Program. Fulbright is a competitive educational program in the U.S. that offers international opportunities to scholars and professionals to research, teach and learn.

J. William Fulbright, founder of the program, was a U.S. senator and was the longest serving member in the history of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. It was his goal to create an international exchange program in order to offer scholars the opportunity to explore differing cultures and societies from all over the world.

The program, which is sponsored by the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the United States Department of State, currently operates in over 160 countries.

At Xhuvani, Vanwesenbeeck taught three courses: Gender Studies, Research Methods and Thesis Supervision.

Initially, Vanwesenbeeck had planned to focus on American drama and American women writers.

Showing off a photo of her and her students flexing their muscles during a surprise party they had thrown for her on her last day, Vanwesenbeeck talked about the curriculum she ended up teaching.

“Before I left, I had some idea of what I would be doing and my proposal for Fulbright was based on what I would be willing to do, but the host institution in Albania has a set curriculum and they have their own semester-to-semester needs,” Vanwesenbeeck said. “Because I really wanted to teach women writers, I asked if I could combine American Women Writers with Gender Studies and divide up the 15-week semester into two. The first seven weeks, teach theory, and the seven weeks at the end of the semester, do nothing but read literature.”

When considering location for her scholarship, Vanwesenbeeck had very specific standards. In 1990, the communist regime in Albania collapsed, and the country entered a period of economic and social unrest.

“Before I had even started my application, I had two countries in mind: Mongolia and Albania,” Vanwesenbeeck said. “Those two countries have similarities that I was looking for in a grant. [The countries are] radically isolated. In this case, they have a communist past and then they shed that communist skin in the 1990s and both start diplomatic relations with the U.S. In Albania’s case, they see very quick integration into the Western culture, into capitalism and for me that was, by all means, one of the most important criteria when I made my selection.

“I wanted to be in a place where, in this case, was at the heart of Europe. Albania is 45 minutes away from Rome and if you’re in a car, two hours away from Greece,” she said. “It’s at the heart of Europe, and yet, it’s not part of the European Union. Anomalies like that made Albania very attractive to me.”

In addition to teaching at Xhuvani, Vanwesenbeeck also organized two roundtables on gender issues in her hometown of Elbasan.

One of the roundtables focused on women’s health and was held during the Cervical Cancer Awareness Month of January. The discussion drew in a crowd from the community as cervical cancer is one of the primary causes of women’s mortality in Albania.

While Albanian healthcare is still catching up, women often don’t have the means for basic preventative care. Pap smears and breast cancer screenings are currently not routine for Albanian women.

“I think my students were grateful that we took some time to educate ourselves,” Vanwesenbeeck said. “To much of my surprise, most of my students did not know about the issues in their country.”

The second discussion will coincide with International Women’s Day on March 8 and will discuss justice relating to Albania’s ongoing legal reforms.

Today, Vanwesenbeeck will be discussing her time in Albania during a campus-wide lecture at noon in Williams Center 204D.

“I really want to talk about my host institution and my classes and what I accomplished on my Fulbright,” Vanwesenbeeck said. “But I also want to talk about the stories that I brought back with me. People I’ve met, some of their stories that stayed with me, and I hope, and I’ll try really hard, not to give generic, textbook information about the country.”

In an article written for the Dunkirk Observer, Vanwesenbeeck wrote about the appreciation she has for the small neighborhood she was fortunate enough to live in.

“I have come to appreciate the neighborhood vibe here,” Vanwesenbeeck wrote. “I like seeing the same old couple take walks, hand in hand, at the same morning hours, or talking to the old lady on my street, who asks me for a big screen TV (she sells socks), my hairdresser who is a big Marilyn Monroe fan, my baker who remembers which bread I like and my supermarket vendor who always waves at me as I walk back from school in the afternoons.

“My starting point is that I had no way of knowing what the country is or what Albanians are like,” Vanwesenbeeck said, “so I want to talk about my small street and all of the people that I talked to on a daily basis and what my life was like both in the classroom and on the streets in Albania.”