JULES HOEPTING

Managing Editor

During the first week of the fall 2020 semester, Justine Bloom walked around campus and came across the carcass of a bird. The body was on the concrete below the northern wing of the Michael C. Rockefeller Arts Center building.

Bloom, a sophomore Earth studies major with an environmental studies minor, walked past the building the next day and noticed two more dead birds. Two days later, they found two additional bird carcasses.They instantly became dedicated to decreasing the number of deceased birds.

“Every day it felt like I would come back and there would be another bird. It was bad the first couple of weeks last year,” Bloom said.

They brought up the matter with Biology Professor Jonathan Titus, who ran the greenhouse internship Bloom was taking. Titus told Bloom he had been noticing the dead birds for years and, despite efforts, he had a hard time convincing the campus to take any precautionary measures; the project had to be student-led, and he was willing to help.

“I had the moment of ‘Wait a minute … I have four years. That’s a lot of time for me to be a thorn in their side about this,’” Bloom said.

Bloom and Titus did their research. They found 3–5 dead birds outside the northern wing of Rockefeller weekly. For each bird, they estimated there were another 10–20 birds that were not seen, because many birds land in the ivy below the northern Rockefeller wing. “There’s a chance that the bird will hit the glass and they’ll be stunned, but they’ll be able to fly off back into the woods and there they’ll die,” Bloom explained.

A spectrum of birds are affected by the windows, from small finch-sized birds to robin-sized birds. Most of the birds killed are migratory birds.

The majority of the bird collisions occur during the mid-seasons of fall and spring. “That’s when your major migratory patterns start picking up because we are in the middle of a major migratory route … There is a higher concentration of birds passing through, which is why we get such elevated numbers of bird strikes around Rockefeller in particular,” Bloom said.

Another reason the carcasses are accumulating at Rockefeller is because its windows are significantly more reflective than the other windows on buildings on campus. Birds see the reflection of their habitat — the campus woodlot — and think they can fly through the frames.

When examining options to prevent window collisions, several solutions emerged. Some options included an expensive type of glass with a pattern invisible to humans but helpful to birds, the installment of zen curtains — spaced strips placed outside windows — and the application of white opaque line or polka dot vinyl stickers. The chosen option was the dot stickers, which needed to be a quarter-inch or more in diameter and spaced two inches or less apart in order to be effective.

“The birds don’t see the glass, they see a space they can fly into or a reflection of their habitat. So, when you put the dots there, you’re breaking up the space and then they’ll see the dots and they’ll look at the space inbetween the dots and consider [if they] can fly between [those] dots,” Bloom explained.

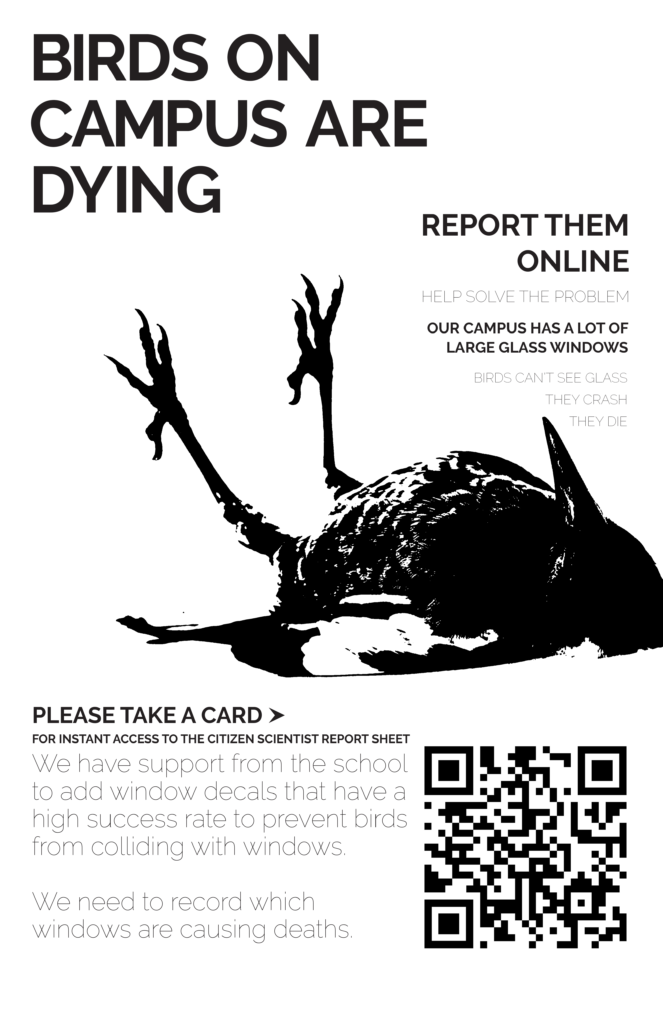

Once Bloom had the numbers and a solution, they started “absolutely plastering the hell out of the Rockefeller Arts Center with posters.” These posters used “assertive, some people will say aggressive” language and a visual of a bird carcass to capture viewer’s attention.

Bloom also sent out emails to “people [who] are either campus authorities or faculty in the department where [the dead birds] would be relevant, like the art department. And a couple people on the sustainability board.”

Barbara Racker, Marion Art Gallery director, contacted Bloom after seeing a poster. Racker sympathized with Bloom’s frustrations and wanted to help Bloom find grant money to bring awareness to the issue.

After Titus consulted several bird enthusiasts, Scott Weidensaul, a renowned ornithologist, was selected as a guest speaker to lecture on the astonishing features of migratory birds. Sponsored by the Carnahan Jackson Fund for the Humanities of the Fredonia College Foundation, the Cathy and Jesse Marion Art Gallery and the Department of Biology, the lecture brought in over 70 people from the Fredonia campus and community on Sept. 23, 2021. In addition to taking the audience on an imaginative tour around the world via wings, Weidensaul was sure to mention Rockefeller was a migratory bird killer.

In fall 2021, Jason Dilworth, an art professor teaching Graphic Design 5, presented his class with an assignment: create awareness about the dead birds.

“I was interested in having art students approach it and say ‘What is the problem? How can we utilize design to help create action?’” At the end of the semester, the students will be assessed on how well they used their design skills and if their efforts led to any results.

Bloom spoke to the class on the topic and inspired the students so much that “even though the project is [now] over in class, the students are still working on it and [are] passionate about the project,” according to Wilson Thorpe, a senior graphic design major.

Dilworth had been aware of the dead bird issue for years. The class’s project came after a meeting Dilworth attended where students, professors and faculty discussed the ongoing bird deaths.

The following people attended the April 8, 2021 meeting: Bloom; Titus; Chloe Petry, a science major who graduated in spring 2021; VANM professors Dilworth and Pete Tucker; Sarah Laurie, director of Environmental Health and Safety and Sustainability; Markus Kessler, director of Facilities Planning; and Michael Metzger, vice president of Finance and Administration.

Dilworth’s takeaway from the meeting was that specific local evidence was needed in order to get stickers put up on a window, despite plenty of existing national data that windows nationally kill billions of birds. He understood that the project needed to be student-led and wanted his students to generate awareness.

Instead of “getting a job at a major multi-national corporation, I’d rather see a student saving birds,” Dilworth said.

If the solution was as simple as putting stickers up on windows, why was it so hard to do?

The Facilities Planning staff created an entire report addressing the application of Bird Strike Film, or vinyl polka dot stickers. Within that report, multiple concerns were raised.

In 2019, a Rockefeller window project included the replacement of the windows on the second and third floor; A 10-year warranty was submitted for the glass of the windows. The application of stickers would violate the warranty because the stickers would add an abundance of weight to the windows.

According to the Bird Strike Film report, “If there were to be a seal failure on one of the insulated glass units after the installation of a bird strike film, the window/glass manufacturer could claim that the seal failed due to something that occurred during the film’s installation or claim that the added weight of the film caused the seal failure. This would then put the replacement and repair costs of the failure as the responsibility of the campus.”

Bloom questions how often this warranty is actually used.

Adding stickers to the windows would also have to be approved by the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO). Because Rockefeller was originally designed by the famous architecture firm I.M. Pei and Associates in 1965, “SHPO will take an interest in and need to be consulted on the selection of the pattern for any applied window films,” according to the report. “SHPO’s review process allows for one month of their review prior to comment of approval after the date of submission.”

In addition to warranties and SHPO, there is the issue of funding the sticker purchase and application. If the project was to be funded through state university money, the project would have to be approved by people outside of SUNY Fredonia. In order to get the project approved, there would need to be proof that a significant amount of birds were dying from Rockefeller window collisions.

On May 20, 2021, two cameras facing each other were installed on Rockefeller to monitor bird collisions. As soon as an object crosses a certain line, the cameras take pictures and send those pictures to Sarah Laurie, health and safety director.

After conducting research, the cameras were carefully selected and installed by Laurie and staff members of the ITS Service Center. The first camera was installed on the northeast corner of the Rockefeller building near Symphony Circle facing the length of the building.

The second camera is in a tree near the northwest end of the building facing the length of the building.

According to Laurie, as of Oct. 15, 2021, the trail cameras have “recorded zero bird strikes.”

“We’ve gotten a few birds perching on the building or checking out the camera, but none flying into the windows,” Laurie says.

To make the task more challenging, projects funded by the state are significantly more expensive than projects funded by the college.

According to Markus Kessler, the director of Facilities Planning, this is because state projects have a cornucopia of requirements, such as paying employees working on projects a certain wage and contracting out work to a certain percentage of minority-owned businesses. Furthermore, prices are raised because the contractors working on the project would be using their own equipment as opposed to utilizing equipment already on campus.

The Bird Strike Film report states purchasing and applying vinyl stickers would cost between $69,000 to $76,000. That is a lot of money to ask for when there are no recorded bird strikes in over six months.

Another approach would be to use SUNY Fredonia’s funding or other funding. The overall cost would be lower if the university utilized their own staff and equipment to purchase and apply the stickers.

Racker had offered to help pay for the stickers with Marion Art Gallery funds if she is able to “call it an art project and involve students.” Racker has even gotten a $27,201 quote for the purchase and application of the vinyl stickers from Southpaw Signs and Stripes in April of 2021.

This solution may seem simple enough, but applying the stickers is more difficult that it seems. According to Kessler, the stickers come in individual rolls as opposed to large sheets. If the stickers are applied incorrectly they might not last as long as they are supposed to. If the college provides its own application, there is no warranty in place if anything happens to the stickers Thus, there is a strong chance the stickers will need to be applied again sooner than if the stickers were applied by professionals — hence why going through state funding is still strongly considered an option.

In order to put up stickers with Fredonia’s funds and labor, the project would need to be passed by Michael Metzger, vice president of Finance and Administration. On Oct. 15, 2021, Metzger’s response via email to a question about the status of sticker proposal was the following: “We installed trail cameras outside of the windows to monitor. The cameras have been installed for about six months and to date not one bird has hit the windows. In addition, we periodically check the ground below the windows. We will continue to monitor.”

Kessler stressed that the facilities staff believe people when they say they are seeing the dead birds on the sidewalks near Rockefeller. People’s natural assumption is that the birds hit the window and fall to the ground. But how do the observers know the carcasses were not moved from where they originally landed? Where is the evidence?

Students and faculty dispute administration suggestions that the birds are not dying or that they are being moved from elsewhere. They also recall that spring and fall are the primary migration periods, rather than summer.

Dilworth and Racker both believe humans created the dead bird problem by putting up the building and it should be the responsibility of humans to fix the problem. They both believe humans need to do a better job of living in harmony with nature instead of prioritizing humans over everything else.

“The Earth is not solely for man,” Dilworth said.

Dilworth stresses that the campus has made sustainability-focused improvements, specifically highlighting the establishment of native plant gardens and no mow zones — designated areas on campus that are not mowed to allow growth of natural plants and species. “I think it’s really important that students understand what’s being done on campus that is helping out,” Dilworth said.

“I don’t think too many people in the administration don’t want to solve [the dead bird issue], but they don’t want to do it if it’s going to take up any time or cost money,” Titus said.

He also points out most environmental change “comes from aesthetic reasons” as environmental change rarely has “immediate consequences.”

“People come up with the science all the time” but “it doesn’t matter that it affects the ecosystem” or people’s health, “people’s opinions are because of aesthetics,” Titus said.

He believes “The way this is going to move is through student actions, making the administration think this is something they need to work on.”

So, what can students do?

Bloom advises students to “be aware of the birds on the ground. Record them as you see them. Make a fuss.”

Students should photograph bird carcasses exactly where the bodies are found and send the image and a specific description of the carcass location to Bloom (bloo0218@fredonia.edu). The birds should be documented as soon as they are seen because some bird carcasses remain on the ground longer than others.

Bloom advises students to pull down the blinds and turn off the lights when they are not using a room because this can help prevent bird collisions, although stickers are more effective.

More than anything, students need to continuously talk about the bird death issue so that it cannot be ignored. Dilworth recommends visiting 3billionbirds.org to learn more about the topic from a national perspective.

“Justine is a catalytic type person — she makes things happen,” Titus said.

“This is something I really do care about and I want to see success and I want dots on those windows by the time I graduate,” Bloom said.

But Bloom cannot do it alone. The sticker project will only happen if many students continuously pressure the administration.