ALYSSA BUMP

Chief Copy & Design Editor

Content warning: This story includes depictions of sexual assault and suicidal ideation. But it ends with hope.

April is a month normally associated with the summoning of spring songbirds and sprouting plants. But for me, April is a month I routinely have to bury my past deep within the soil of my soul.

In the center of my one-bedroom apartment, a dark wood plaque with the words, ‘BRAVERY AWARD,’ engraved in large letters rests neatly on the wall. The plaque is only about six inches tall, but its presence is a heavy reminder of the assault I survived.

In 2018, I was 16-years-old, and I went to a party hidden in woods between tall trees and thickets. I remember getting out of my friend’s car and trudging through the thick April mud. I was determined to make it to the cabin lit up with lights and music down the isolated driveway.

I have always sought escape — a hobby to pass the time, a thought to cling onto that is not my own. At this time in my life, my escape lied at the bottom of a solo cup or at the end of a joint.

But after I had decided I was tired, after I had decided to stop pouring drinks and lighting matches and swaying to the music, I decided to lay down. I decided to go to sleep, or maybe sleep decided to come to me.

Something else came to me that night — unwanted hands, unapologetic and unforgiving touches.

I remember waking up and feeling my insides burning, feeling the sweat of my hands and the filth of the abandoned party around me.

I remember saying ‘no’ — since I know, oftentimes, people care more about if someone says ‘no’ rather than ‘yes.’ Yet nothing stopped.

I remember hearing footsteps and laughs as this nightmare unfolded around and inside me.

Yet nothing stopped.

My rape was not the worst thing that has happened to me. The worst came after.

I grew up in a small Allegany County town, and my class only had 60 kids in it. Everyone knew exactly what had happened to me the following Monday when the homeroom bell rang. I could tell by the way the air stood still, the way heads moved as I walked and voices switched to whispers.

Before I even had time to process what had happened to me, everyone and their mother knew some version of what had happened that April night. I don’t know how to explain it, but their knowledge of what happened to me proved to be another assault on my body, my privacy and my autonomy.

But I still got ready for my second period gym class with my rapist. He immediately looked me up and down, and then whistled at me. I left and barely made it to the locker room where I puked.

After a day or two, I was called into the principal’s office and asked if I would like to talk to the authorities and press charges regarding what happened. I was also informed that I needed to tell my parents within the next 48 hours what happened to me.

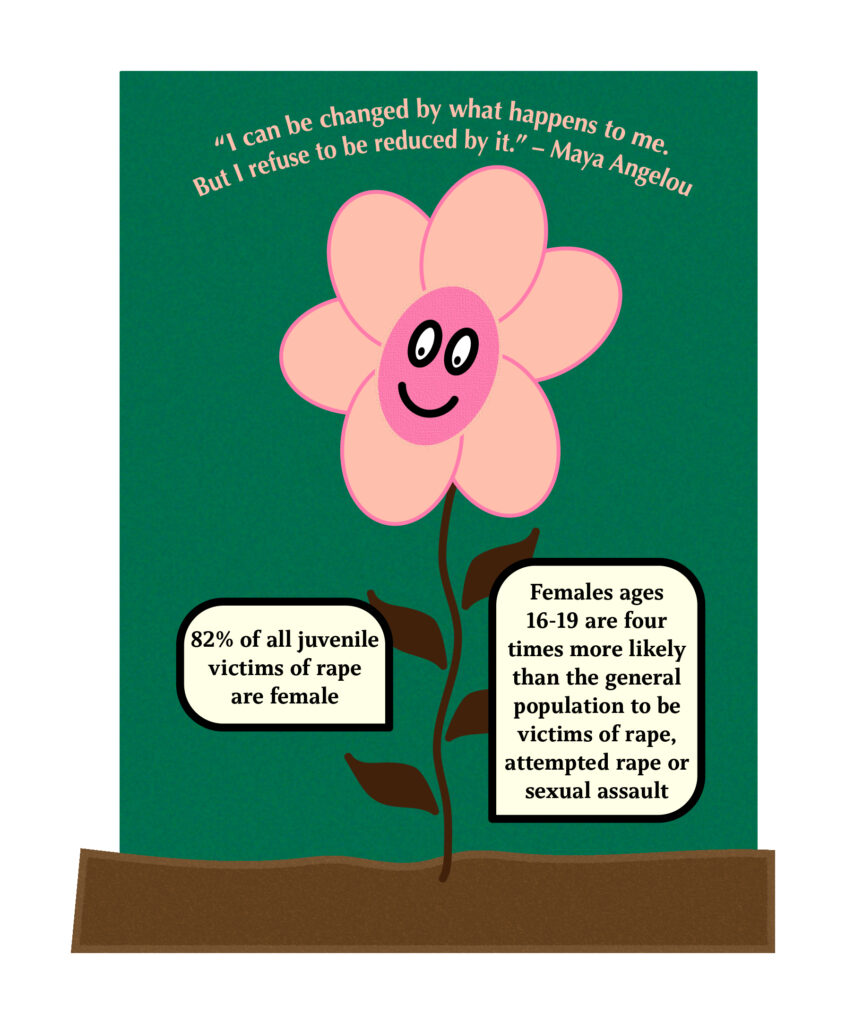

I always knew statistics for rape, sexual assault and abuse are staggering. This is because I am also a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. But in case you do not know, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, 82% of all juvenile victims of rape are female, and females ages 16-19 are four times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape or sexual assault.

I never had a chance to report my previous abuse — I was too young, too disoriented to fully understand. But this time, my assailant wasn’t so lucky. I knew no matter how much I did not want to, I had to come forward and report my case. After spending hours in the police station, handing over my phone for evidence and talking until the hot coals inside my chest turned cold, my 19-year-old rapist was charged with third-degree rape and acting in a manner injurious to a child. Because New York State’s legal age of consent is 17, anyone under the 17 is legally incapable of providing consent to sexual relations. This meant as a 16-year-old, I was legally unable to consent regardless of the fact I was incapacitated.

I met with my prosecuting attorney and victims’ advocate a number of times during the year my case was filed. In between appointments at the courthouse and trying to maintain my sanity, I was harassed by several of my peers. Freshmen — students I didn’t even know by name — would prank call me and pretend to be my rapist. The boys would not stop calling me until I answered the phone, and when I picked up, they would explicitly describe how they would assault me.

The phone calls continued for months, and when I reported them to the cops, they suggested I change my number. I didn’t think the harassment had anything to do with the digits of my cellphone, but rather the graphic and disturbing threats I was receiving. After pleading with the police to take these threats seriously, three of the students were caught.

The trial for my rape case finally came, 10 months after my assault during the coldest days of February. My rapist took a plea — the class E felony rape charge was dropped to a class A misdemeanor of acting in a manner injurious to a child. He was only required to serve 105 days in jail. He did not have to join the Sex Offender Registry, and his record does not indicate he committed rape.

I wrote a victim impact statement to read at court. Similarly to pressing charges, I did not actively want to write this statement, but I was terrified of how I would feel if I said nothing at all. I wanted my rapist to know that even if he got off with this plea, he is still indeed guilty.

These are some of the words I spoke on that gloomy day, as I stood on my own two feet alone in the courtroom, and faced my rapist:

“As a 16-year-old, I had to endure so many things I did not deserve. … I did one of the hardest things to do after being raped, which is report my story. I found something inside of me, something tiny, a glimmer of light, I suppose. But soon, that light burst into flames, and I realized how angry I truly was. … This feeling of anguish I never thought could be distinguished. But even though it felt like I was on fire, that hell had come into my life and completely taken over, I did not lose hope — I gained it. After everyone found out what happened to me, I faced backlash and found myself wondering if I did the right thing. But I still pursued what seemed like the impossible for 10 months. My life was put on hold as I waited to see if what you did to me would have consequences. And in the end, I found justice. I found myself here, in a situation I would have never predicted for myself. … I hope you see the damage you did to me behind the courage I hold. I will never be the same, but who I am becoming now, after being raped, after being betrayed, after everything, is someone strong. I am becoming more and more hopeful, and despite everything, I am healing.”

My victim impact statement is the reason why I won the 2019 National Crime Victim Rights Week Bravery Award from the Allegany County District Attorney’s Office. My victims’ advocate called me two months after my case closed to tell me the good news. But this news didn’t feel good.

To be quite honest, a Bravery Award felt like another fire began to bloom in my bosom, spreading to every corner of my skin. I was angry — I did not feel brave. I felt like a fool.

But still, I drove my tiny gray 2003 Hyundai Accent to the jail my rapist would soon be serving his sentence at to receive my award. Even though two months had passed since my case closed, my rapist would not be in custody until he finished his first year of college. This was part of the plea he had agreed to; the plea that I never had a say in.

Five years ago, on April 28, 2018, I was raped. I find it quite ironic I was raped during National Crime Victims’ Rights Week. I find it even more ironic I was honored with a Bravery Award a year later during that same week in the jail my rapist should have been at — not me. I realized I felt more like a prisoner than my rapist probably felt at that moment, miles away at college.

I am a firm believer that we do not always have control over what happens to us, but I believe we hold all the power in how we react. I suppose my Bravery Award is a constant reminder of this, but it is also a reminder of how I felt in that jail that day, when my rapist was free.

I have spent years of my life hating the fire that burns inside of me, the fire I spoke of in my victim impact statement. But on the bottom of my Bravery Award, a quote by Joshua Graham reads, “I survived because the fire inside me burned brighter than the fire around me.”

I’ve thought about this quote a lot during the past four years. I believe all of us hold a light within ourselves that can carry positivity, passion and energy. My inner light has repeatedly burst into flames — from pain, from rage, from self hate — consuming all that I am. These flames burn and sting; the fire hurts then heals. And after four years, there are countless times I’ve risen like a phoenix from the ashes of my old self.

I did not rise from these ashes alone, though. This is not a story about suffering or sorrow. This is a story about stoicism, about defying the odds and the statistics. This is a story about how I could have never survived without the support I received.

Jane Goodall wrote in “The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times,” “Hope is often misunderstood. People tend to think that it is simply passive wishful thinking: I hope something will happen but I’m not going to do anything about it. This is indeed the opposite of real hope, which requires action and engagement.”

Hope requires us to act. Because of the actions of others, I have realized there is more good in this world than there is bad. I wholeheartedly believe this — I want you to believe this, too.

But for a long time, I did not see myself when I looked in the mirror. Instead, I saw my 16-year-old self looking back at me: The 16-year-old who was raped at a party with bystanders everywhere. The 16-year-old who came to school that next Monday, and everyone already knew about the worst thing that had happened to her.

Actions of altruism have convinced me to cling to hope during my darkest times. I often remind myself of the two boys in my high school who drove me to the police station to report my assault. Another high school boy compiled evidence to support my case immediately after hearing my story. He is now pursuing a law degree to help survivors like me.

I remind myself of my victims’ advocate who was truly inspired by my bravery enough to recognize me for it. After I read my victim impact statement at the ceremony, a woman told me in between sobs and sniffles that I was so brave — braver than her because she never reported her assault.

I remind myself of the empathetic girls at school who would console me between tears in the bathroom stalls. I remind myself of my high school math teacher who refused to let me fail physics my senior year because he knew I was too smart and too strong to give up. And I’ll never forget my high school English teacher who helped me write my victim impact statement and recommended I attend Fredonia for journalism.

I did not always have hope, though. Hope and grit are difficult to sustain during trying times. During my first semester at Fredonia, I was convinced I had lost all hope. After barely surviving high school, college felt too nauseating to comprehend.

August came and went. I moved into Hemingway Hall, but I never felt at home. September unapologetically ran away from me, stealing all hope I had left. By the end of October, I decided my life was too much to bear.

While most of my peers were enjoying their first Halloweekend, I spent six days in a now-closed psychiatric center.

After I was released from the hospital, I was certain I would drop out of college. I believed I didn’t belong at Fredonia — or anywhere for that matter. I had plans to inform my academic adviser, Elmer Ploetz, that I would not be continuing higher education. That was until he told me about The Leader.

The Leader undoubtedly saved my life. Nights I otherwise would have spent alone, aimlessly drifting between thoughts of failure and doom, I wrote stories about this campus. I wrote stories about resilience, hope and determination. These stories mattered deeply to me — but they meant even more to my subjects and readers.

Jessica Meditz, who was first my editor but soon became my close friend, encouraged me to continue writing for The Leader. Her downstate Queens attitude inspired me to embrace myself. I followed her footsteps up the ranks from Life & Arts Editor to Editor in Chief. By the time I was a junior, I was in charge of Fredonia’s student-run newspaper.

Jules Hoepting, The Leader’s previous Managing & Design Editor, and I took control of this paper the year after the pandemic. Jules allowed me to see the world from a new perspective of wonder and curiosity. I found great delight that the two of us would lead The Leader, but I also felt an exuding amount of pressure to build this paper into something bigger than ourselves.

I refuse to say that running this publication has been easy — these past two years have been full of challenges, mistakes and obstacles. But with every difficulty, I have learned important life lessons. More importantly, I have learned to hold hope for the future.

Will Karr, The Leader’s current Editor in Chief, joined our staff in Fall 2022 with burning enthusiasm and energy. His genuine desire to build community and cultivate kindness have allowed me to grow into a better leader. After spending a year and a half as Editor in Chief, I was excited to see Will step into the position in Spring 2023.

Almost everyone I’ve interacted with at Fredonia has cemented that I need to stay true to myself. Of course, there have been negative experiences, but I have decided the positive outweigh the negative.

Before I found supportive students on campus to lean on, my professors gave me their compassion. There are so many mentors here who have made a significant difference in my life: Elmer Ploetz, Dr. Natalie Gerber, Vincent Quatroche, Dr. Amanda Lohiser, Dr. Sue McNamara, Dr. Kim Marie Cole, Dr. Jeanette McVicker and so many others that deserve recognition.

When I feel close to self combustion from the wildfires abroad and the flame in my belly, people here reaffirm I cannot go out in a plume of smoke.

I could not write this story without telling my truth about my assault, but my assault is such a small part of my story. I have built my life to become so much more than that stormy April night. Often, survivors are terrified to speak about their experiences because our society often punishes survivors more than the perpetrators. I have learned we must speak out anyways, despite the backlash we might face.

April is the month of rebirth and triumph, despite its turbulent weather. I see the budding daffodils bringing color back to the bleak landscape; their green stalks dare to break through the cold mud. April is a reminder that after a frigid, harsh winter, life prevails.

I won the Bravery Award by using my voice alone in a courtroom. Four years later, I earned the 2023 Lanford Presidential Prize by being a voice for a community. Although this prize honors one graduating senior, I earned this award through the stories my subjects have shared with me. Their vulnerability and courage to share their stories is why I am sharing mine today.