WILL KARR

Staff Writer

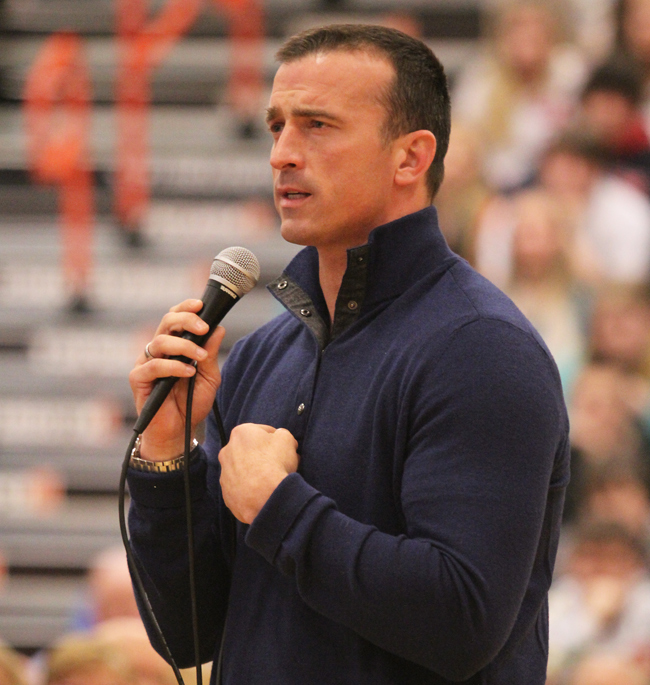

Growing up, former NCAA and NBA basketball player Chris Herren would attend school assemblies where guest speakers would talk about drug addiction. At the time, he never thought he would one day be talking to auditoriums of students about his own battle with addiction.

“I remember some 35-year-old man talking to me about substance abuse, I remember saying to myself that I would never be that guy,” Herren said.

Herren has spoken in front of numerous national sports teams, including the New England Patriots, Green Bay Packers, New York Jets, Boston Red Sox, all the way to ivy league colleges like Harvard and Yale. However, in recent years, he’s been speaking more to high schools and general college students.

Last week, Herren visited McEwen Hall on Wednesday, Sept. 14 to give a lecture about his latest film project, “The First Day,” which talks about his personal journey with recovery. In addition to Fredonia, he traveled across Chautauqua County to speak to students at 12 out of the 18 school districts, as well as Jamestown Community College.

Through his efforts, he is hoping to overall change the way that addiction is perceived and approached.

“When it comes to addiction, I think we’ve gone terribly wrong in the way that we talk about it,” Herren said. “We put so much energy and focus into the worst day that we forget about the first day.”

Herren grew up in a home surrounded by alcohol in Fall River, Mass. While his father was known publicly as a politician by day, he was an alcoholic behind closed doors at night. Herren began to significantly resent his father and the way he acted when he was drunk.

Years later, at the age of 13, he took his father’s beers and got drunk himself.

“I watched the beers my father would drink hurt my mother,” Herren said. “To think how much I hated that man as a child.”

Herren began consuming the one thing he hated the most. He describes this event as the first “red flag” decision in his life.

At the age of 18, he went off to college. At the time, he was ranked one of the top 20 high school basketball players in America. Sports Illustrated called him with an illustrious offer to be on the cover of their basketball issue. His college friends threw him a party to celebrate the news. At the party, a girl offered him cocaine.

“I promise you, it’s not going to hurt you,” the girl said. “Put a little bit on your tongue, all it’s going to do is make it numb.”

Herren had no idea that only a little bit would lead to a long-term addiction.

“I had no idea that one time would take 14 years to walk away from,” Herren said. “… Four months later, I would be publicly humiliated by every newspaper in New England, kicked out of college and fail four drug tests.”

At the age of 21, Herren was sent to a 30-day treatment center to recover. After leaving, he was drafted into the NBA as the 33rd overall pick in 1999. Life started looking up again for Herren.

“That rookie season was the best that I ever had in my career,” Herren said. “I moved back to Fall River and bought a home.”

However, upon returning home, an old high school friend sold him a pill of OxyContin. One forty milligram pill quickly turned into 1,600 milligrams a day. Herren said that this pill changed his life by eventually leading him to use other drugs like heroin.

During this time, Herren received a call from NCAA coach Rick Pitino saying that he was being traded to the Boston Celtics.

“I grew up in Boston. I pretended to be a Celtic when I was little and fell asleep to them taped to my bunk bed. I pretended to be them in my driveway,” Herren said. “What should have been a dream come true was a nightmare.”

Although Herren’s all-star dreams were finally coming to fruition, all he could focus on was getting his next fix, showing how his addiction consumed him.

“When I start, I can’t stop,” Herren said.

After a non-linear trajectory with addiction, Herren has been sober and clean since Aug. 1, 2008. He now helps others who are struggling, hoping to promote new addiction rhetoric and conversations around substance abuse and early intervention.

“I think it’s a shame that words like ‘rock bottom’ are still being used by people,” Herren said. “We have put in people’s heads that those suffering from drug and alcohol addiction have to lose everything before they come back. And that’s just not true.”

Herren said that the average stay at a treatment center is 12 days, not leaving patients much time to recover. He called out a double standard in regards to how drug addiction is handled compared to other issues.

“If I go to a local hospital and say I don’t want to live anymore … they’ll hold me for 72 hours,” Herren said. “But if I walk out of the room right now, shoot heroin, overdose and go to that same hospital … they’ll put me back out on the streets two hours later. How does that make sense?”

Today, many people believe that addicts don’t deserve treatment. When Herren was once hospitalized for a heroin overdose, the nurse said, “We have people in the waiting room who deserve to see doctors and he’s not one of them.”

Herren explained the way the healthcare system is built essentially encourages addicts to relapse. However, he is working to change this system.

He founded his own recovery center, The Herren Wellness Treatment Center, in Massachusetts. The center currently has 36 patients and provides them with longer term treatment. Overall, Herren is using his platform to inspire others and to raise awareness.

“With basketball, I went to the gym everyday [to stay] sharp. It’s all about repetition and numbers,” Herren said. “… I’ve taken that mindset and put it into recovery.”